The Toyota Production System is a system built around minimizing three factors influencing a process: Muda (waste),Mura (variation) and Muri (overburden). These three together form the 3M Model and had a huge influence on my book Lean Transformations. This article offers is a copy of a chapter of the book, which gives some more theory on Mura – variation – and how to reduce it. It is Variation exists in many forms and influences efficiency of a process in multiple ways. There is variance in customer demand, variance in product mix, variance in production methods within a plant or within processing times and variance in way of working (Panneman, 2017).

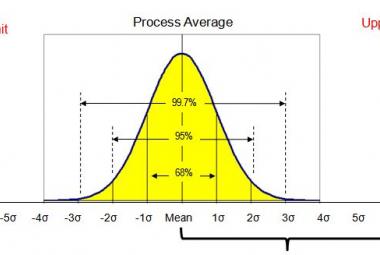

Hopp & Spearman (2000) describe, among others, the following two laws concerning (production) variance:

- Variability will always degrade performance of a production system

- Variability in a system will be buffered by some combination of inventories, capacity or time.

To reduce the these types of buffers, there are roughly two things you can do: reduce variation in customer demand (1) or reduce variation in your processes (2).

Influencing the VARIATION OF CUSTOMER DEMAND has everything to do with cooperation in a supply chain. When organizations in a supply chain do not share information about customer demand or inventory levels, the bull-whip effect emerges whenever customer demand fluctuates. This effect describes how a small change in customer demand from end customers can lead to a high change in order size upstream in the chain, which in turn leads to large inventories in the overall supply chain. Each link in the chain will have the tendency to order “extra” when an order can’t be met due to an unexpected shift in customer demand, especially when a backlog exists. The longer the total lead time in the supply chain (hence, delivery times between the links) , the higher the bull-whip-effect. Also, the higher the number of links in the chain, the higher the bull-whip-effect. In this sense, each link in the chain is a customer of the link upstream in the chain.

Three recommendations to reduce the variation of customer demand are:

- Reduce the number of links in a supply chain. External warehousing or moving parts of a plant is not a good idea in this sense.

- Reduce delivery times between links. Offshoring across the world? The possible six weeks of transport times are killing for inventories and lead times in the chain.

- Create transparency between links in the supply chain when it comes to order portfolios. This will reduce the tendency to increase the order size at every link.

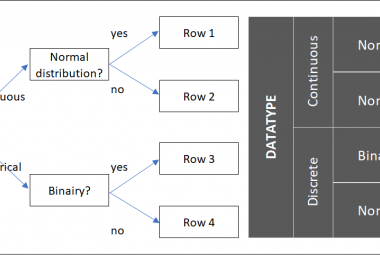

There are different methods to reduce VARIANCE IN THE PROCESS. The variation in product mix has relatively low impact on a production process when the processing times are balanced for different products. There are at least four methods to reduce this form of variance: Modular product design at design level (1), Production leveling in production planning (2), building Flow at production-level (3) and standard work and 6S on workstation level (4).

At the level of production design, the variation between products can be minimized by using modular designs. Using standard modules will reduce the number of possible material routings in the factory and a number of inventory items. One example of modular design is a series of wardrobes at IKEA where a choice between a number of drawers, doors and handles lead to a relatively large amount of combinations for end customers to buy.

A method to reduce the impact of customer variance in the production planning is the (Lean) tool Heijunka (production-leveling). With Heijunka one defines a fixed interval in which all product types can be produced. The shorter the intervals, the more often a product is produced and the shorter the lead time of each product will be. Because the lead time is reduced, the uncertainty in customer demand reduces as well. When yearly customer demand is cut in smaller pieces, changes in customer demand can be smoothed out between the different production runs. To implement Heijunka, changeover times should be minimized to minimize cost of changeovers. A tool which can be used for reducing changeover times is SMED (Single Minute Exchange of Die).

Next to optimizing product design and production planning, the way products move through the plant should be optimized. Ideally, products flow through the plant, which means products never have to wait to be worked on as they move between the necessary workstations. When the processing time of workstation 2 is larger than workstation 1, either every product coming from workstation 1 has to wait before station 2 can work on it, or station 1 has to wait for free capacity at workstation 2. A graphical way of visualizing the line balance is the Yamazumi.

At workstation-level all operator handling should be optimized to minimize production variation. Standardizing procedures and lay-out prevents different work cycles for different operators performing the same task and employees to search for materials or tools they need. Standard work describes the safest and efficient method to perform a certain sequence of tasks while 6S describes the safest and most efficient lay-out for a workstation. Reducing variation is one of the reasons Standard Work and 6S form the basis of every Lean implementation, which is why they are the foundation of the Lean House for the Shop-Floor.

Reducing Mura (variation) is important for every Lean organization. Variation is always buffered by either inventories, capacity, time, or a combination of those. More Mura therefore leads to more Muda (waste). Eliminating waste will lead to higher results if variation is also reduced. By applying (a number of) the tools described in this article, the impact of variation on any production process can be reduced. The lower the impact of variation on your process, the higher the flexibility to respond to changes in customer demand.

This is 4/4 from the series ‘The 3M model’

Continue to:

Hopp W.J. & Spearman, M.L., 2000, Factory Physics, sec. edit, New York: McGraw Hill (order this book)